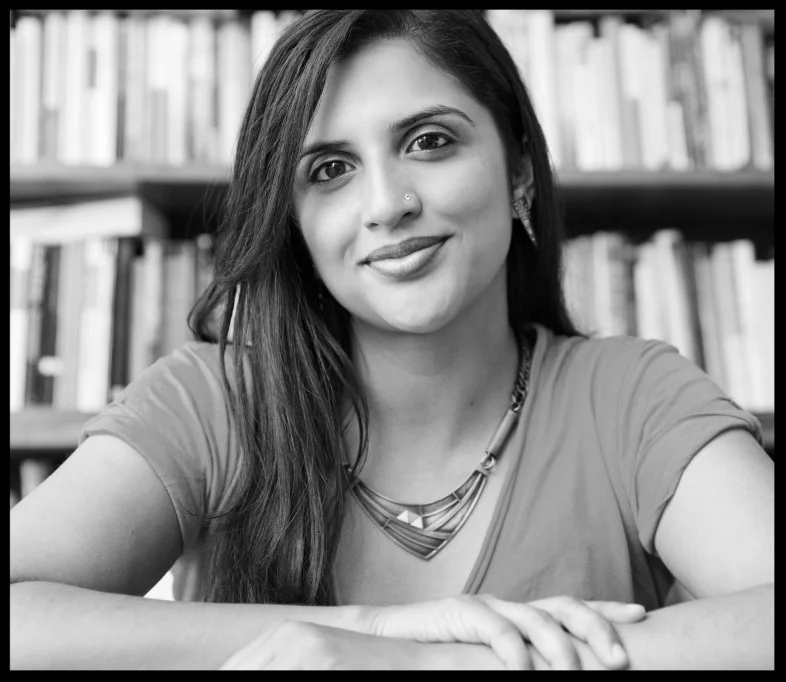

By Caitlin Herron

Carmen Gillespie gladly finds time to discuss the importance of questions and [re]creation of historical figures. These ideas are central to the evolution of her latest poetry collection, "The Ghosts of Monticello: A Recitatif" (October 2017), winner of Stillhouse Press' 2016 Poetry Contest.

Despite a busy week taking care of her 10-year-old and the close of George Mason's annual Fall for the Book festival, Gillespie found some time to speak with me about her inspiration for her new book and what brought her to this moment in her writing career.

Although she has always written poetry, and can’t imagine her life without it, Gillespie says her love of the form has been deeply intertwined with her academic pursuits over the last 15 years. “In academics, I tend to focus on black female writers. There is so much that is still covered that needs to be excavated,” says Gillespie, English professor and director of the Griot Institute of Africana Studies at Bucknell University and the author of several books of poetry and critical works.

Part of what motivates her work in both poetry and Africana studies are questions, she says. “Sometimes poetry and academics have the same questions but not the same answers, and sometimes poetry is more effective at answering them.”

This was certainly the case while attempting to answer some of the central inquiries about the life of Sally Hemings, Thomas Jefferson, Martha Jefferson, and others featured in her collection. Primarily, Gillespie wanted to explore the idea of whether or not Hemings had any agency in her story, especially in her relationship with Jefferson, the third president of the United States, with whom Hemings was thought to have had six children. “I can’t believe that every encounter she had with Jefferson was about violence. My understanding of human beings is much more complicated than that, so that is what I wanted to explore,” Gillespie explains.

But she did not stop with Jefferson. Gillespie also wanted to expand upon what Hemings' relationships might have been like with others on the plantation, given her position as both a slave and the lover of such a powerful character. “So many people have said so much about Jefferson, but it was interesting to me to focus on her other relationships with her mother, Martha Jefferson, and her half sister, and how that dynamic would work if they were to have a conversation,” says Gillespie.

She sees her collection as a dynamic story, and one which she hopes “makes the link between our contemporary situation and the paradoxes of the past.”

Interestingly, this questioning of the past in Gillespie's collection is formed by language that was originally written to be sung on-stage. "The Ghosts of Monticello" got its beginning as a libretto for an opera performed at Bucknell University, where Gillespie enjoyed engaging with the actors and musicians. “I am inspired, energized, and sustained by theater, dance, and music performances,” she says, noting that when composing something for people to sing versus developing the structure of a collection, the writing can be quite different.

For those thinking about writing fictionally or poetically about history, Gillespie offers some choice advice. First, she says, research is critical. “If you are going to write about something that actually happened, it is really important to know your subject well... People are often afraid to do that research, and think it will inhibit the imaginative experience, but I don't find that to be the case.” Second, she emphasizes how important it is to be “an observer of human experience and understand how people interact.” Says Gillespie, “Ask the questions: what does it mean to experience grief or lose a child? Once you start thinking about these things, the characters speak to you rather than you having to create them.”