By Evan Roberts

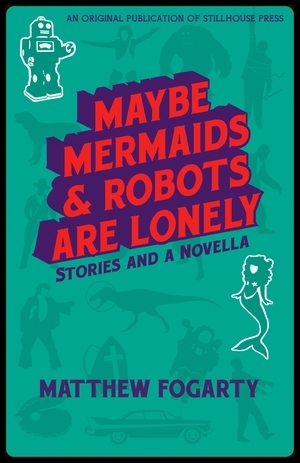

“I've always wanted to write and I've always written,” says Matthew Fogarty, author of Stillhouse Press’ forthcoming Maybe Mermaids & Robots Are Lonely. More than half a decade ago Fogarty practiced law during the day and squeezed writing into his schedule in the wee hours of the night, though writing proved far more fulfilling and enjoyable; eventually this manifested in his decision to leave his job and pursue an MFA in creative writing. “It was the hardest, riskiest choice I've ever made, to go from a comfortable living in a promising career to earning next to nothing devoting my time to trying this thing I could only hope I'd get good at.”

Fogarty says he didn’t consciously develop his writing style. “As a writer, you're the product of what and who you read, [and eventually] you reach some kind of critical mass when you stop emulating individual writers and you feel the freedom to just start writing like yourself.” He praises George Saunders’ preface to Civilwarland in Bad Decline (Random House, 1996) for instilling in him this sense of freedom and individuality, for granting him permission to write what he personally loved to write, and not what he was expected to.

On the topic of other influential works, Fogarty credits Annie Dillard’s Holy the Firm (Harper & Row, 1977)—and later her other stories—with refining his approach to story-making. “[It's] the way she plays with words and sounds and constructs sentences and rhythms and how she teases out meaning, how she builds characters out of these things, how everything feeds the work as a whole,” says Fogarty, who clings to his own storytelling dogma, a complementary dichotomy formed from the works of Stuart Dybek and Etgar Keret: where Dybek said “anything can be a story,” Etgar Keret said “a story can be anything.” To Fogarty, they’re both right.

The very beginning, the first five or so minutes upon sitting down to start or resume a story, this is the moment Fogarty finds the most difficult, the most precarious. But sometimes, even after he’s worked up a rhythm, there’s an even greater challenge to overcome. Fogarty says there are times “when [writing] feels silly or unnecessary or wrong, or when words don't feel strong enough or when I don't feel strong enough. It's not failure I'm afraid of in those times. I don't know what it is. Maybe something scary about laying the world bare.”

Fogarty is a unusual writer. He believes that traditional realist stories have been written before, and the genre is without—for lack of a better word—magic. “I just refuse to believe there's no magic in the world. To me, there's something very real about the magic in my stories and the magic in the stories of writers like Amelia Gray and Etgar Keret. Stories are opportunities to explore and to dream and to be wowed and to feel new emotions, to think new thoughts, to meet new people or animals or aliens or what have you.”

But for Fogarty the goal of writing isn’t necessarily to write a superb story. Instead, he suggests “the idea is to get something unrecognizable onto the page—something that's bigger than the sum of whatever parts I can collect. I know I’ve done something right when I start to feel some emotion from the story, when it hits me in a place I didn't expect.” In his debut collection, filled with stories containing magical realism, characters like Elvis, Bigfoot, and Zelda exist in our collective unconscious. “These characters are all already created in our minds, and we can all experience these stories in whatever way we want, and while whoever may read these stories can also make these characters their own, there’s something about them that is shared, and in this way we can be bonded." And that, says Fogarty, "is the fun of it all."