It’s one of the oldest idioms in the book world, time-tested and subtly instructive: Don’t take things purely at face value, it says; don’t be ruled by your prejudices; look past first impressions and give second chances. It is perhaps least useful when applied to its literal context.

Read moreThe Galley and The Goal: An inside look at small press publishing & promotion

by Stefan Lopez

So, your manuscript has been selected for publication. You’ve done it! You sold your book! At first, this might seem like the most difficult part of the process. In reality, though, acquisition is only the beginning of a much longer—often time more arduous—path to publication.

At any press, preparing a manuscript for publication and getting in front of prospective readers takes a lot of effort on behalf of both the author and the publisher. From submissions to acquisition, development to release—a year-long process, at least—is an all-hands-on-deck endeavor. So, what should a debut author expect from their publication experience? I sat down with Stillhouse Press director of media & marketing, Meghan McNamara to find out.

“There are writers who just want to put their heads down and write, and leave everything else to others, and we just don’t live in a world where that’s possible,” McNamara says, especially as it relates to small press publishing.

“Since we only publish two to three books a year, we have more of a chance to work closely with the author and really refine their work.”

Perhaps the first thing to know about small press publishing is that it’s not uncommon for members of the press to take on multiple roles, especially when they are first starting out. Unlike the big houses—Hachette, HarperCollins, Macmillan, Penguin Random House and Simon & Schuster—who have a whole host of people dedicated to the many different tasks involved in publication, small presses rely on the resources of a few dedicated individuals.

“My roles have changed so much over time, from book promotion to distribution and wholesale orders, and running the website. It’s kind of a mix of all things administrative and promotional,” McNamara says. For the first year, she said, “during the off season, Marcos [Martínez] and I were often the only ones in the building.”

Though there are positives and negatives to this, the small team size often leads to a greater intimacy with a project, as everyone has a hand in developing and promoting it. What small presses might lack in reach and manpower, the staff makes up for in time and care.

“Our press has more of a craft focus,” she says. “Since we only publish two to three books a year, we have more of a chance to work closely with the author and really refine their work.”

Central to the development and promotional process is the galley (also known as an ARC, or advanced reading copy)—essentially the first draft of the final book.

“First you have the manuscript that goes through the editorial process. Once everyone—author and editors—has signed off on it, we send that draft to the printer and it becomes the galley.”

Just like McNamara herself, the galley serves several functions. On the editorial side, it is the last chance for edits to be made, both internally and externally. Editorial interns use it to make their final edits, scanning for grammar or content inconsistencies that might have been missed in the final manuscript edit.

On the marketing and media side of things, the galley also functions as a first glimpse for prospective media, including advance interviewers and reviewers. Media responses both generate buzz for the book and give the publisher a sense of what a general audience response might be.

Image Courtesy of S.K. Dunstall

Galley covers were once a plain and simple endeavor—often plain brown and printed with the title and author’s name—though small presses like Stillhouse now use the galley as a debut cover run of sorts.

“When Stillhouse was first starting out, someone once told me that it takes a person upwards of three times to see a book before they are intrigued enough to buy it,” McNamara says. “It just made sense we should take advantage of this brand opportunity.”

Thus, the galley cover is, in many ways, the perfect opportunity to start conveying the book’s brand.

“Personal appeal is almost always the best way to find support for your book.”

The author is also on the front lines of promotion. Though this networking might seem daunting to many authors, it’s an integral part of the success of a small press title. Through public readings and interviews, author profiles and social media interaction, an author becomes the face of their book. Behind the scenes, they network with fellow literary contacts and acquaintances to shore up support. If there are blurbs — as the industry folk call a book’s cover quotes — they often come from writers or editors the author has worked with or has reached out to personally.

“A personal appeal is almost always the best way to find support for your book,” McNamara says.

And the support cuts both ways, she adds, noting that the books which find the most support are those written by authors who interact with and advocate for their literary peers.

“People want to engage with you if you’re interesting and active, but if you just start a Twitter account to only promote your book, you won’t get a great following.”

While they wear very different hats within the realm of Stillhouse, McNamara’s advice certainly mirrors that of fellow founding editor, Marcos Martínez.

“It’s important to build a community of readers,” Martínez told me during an interview a few months prior. “People will support you if you support them.”

In other words: the best way to become a successful writer is to develop a community.

“Every author has a following, even if it’s just friends of the writer or people who casually follow their work online,” he says.

The world of small press publishing is exactly that: small. Support others so that when it’s your turn, they will support you.

“The world of small press publishing is exactly that: small. Support others so that when it’s your turn, they will support you.”

Stefan Lopez has an internship with Stillhouse Press,

a Bachelor’s Degree in English from

George Mason University,

and a head full of empty.

Tiny Books: Triptychs IN MINIATURE

By Meghan McNamara

"Superman on the Roof."

Last night I read a whole book in one sitting. It took me 45 minutes. When I was done, I couldn’t stop thinking about the family—the father’s cruelty towards his children, the mother’s complicity, how little resolution I was left with in the end. I thought about the author, and how the dedication suggested that at least some of this book is based on his life, on the death of his own sibling, perhaps.

Lex Williford’s novella-in-flash, "Superman on the Roof" (Rose Metal Press, 2017), is a single narrative, told in ten self-contained stories, nearly every chapter the same line repeated—“after our kid brother Jesse died”—and another memory. Related from the perspective of the eldest sibling, Travis, "Superman on the Roof" is a captivating glimpse into one family’s loss of their youngest member, Jesse, from a rare blood disease.

Amidst the backdrop of 1960s Texas, the language is stoic, and at times stilted, the tenor decidedly southern gothic. Travis describes his brother’s body in technical detail—“spotted with yellow-blue bruises on his chicken-bone knees and elbows and shins, his belly white and round and thumping hard as a honeydew melon”—a kind of affection seeping between the lines: “Hearing him laugh, Maddie and Nate and I joined him, still warm from our beds,” he says. “Maddie punching us hard whenever we bumped or splashed him, three rowdy kids and one sick kid all crowded into a three-tubed vinyl pool from FedMart.”

Unsentimental and poignant in the same stroke, Williford explores the wicked side of grief, how poverty colors loss, and the way death needles its way into the human identity, forever reshaping the lives it influences. The characters are evocative, their collective loss the provocateur for their own cruelty, towards one another and themselves. “It was only right and fair that my father should turn against me,” Travis says. “And all I could do—my father’s eldest son, the one who’d killed his youngest—was to stand silent over the years as my mother and father’s grief and rage twisted itself like tanged thorns into switches, belts and boards.”

Less linear, but no less ambitious, Alex McElroy’s "Daddy Issues" (The Cupboard Pamphlet, Vol. 30, 2017) is a five-story collection that distorts the boundaries of voice, character, and form. The first story, “The Death of Your Son: A Flowchart,” is conveyed exactly as the name suggests—in flowchart form—a brilliant vehicle by which, in the space of just 16 pages, the narrator covers the accidental death of his son at his brother’s careless hand, his long concealed infidelity, and the guilt that weaves its way through both these truths.

An excerpt from “The Death of Your Son: A Flowchart."

Akin to Jennifer Egan’s chapter in PowerPoint (featured in her 2011 Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, "A Visit from the Goon Squad"), the flowchart allows for—and in many ways creates—levity, permitting readers to navigate the complex landscape of a father’s mourning and still come out the other end laughing at the dark comedy contained within it.

McElroy’s stories vary in both form and approach, veering towards the downright experimental, as is the case with the title story in the book. Told through a series of choppy, vignette-like paragraphs, “Daddy Issues” serves as a sort of thesis for the collection, reflecting on the relationships between fathers and their children, on the intricacies and sometimes the banalities of being a parent, and also just of life.

“Anthony Henson’s son screamed in the night. He did not know how to raise his son by himself—but to whom, he wondered at night, lying in bed beside his son and massaging his neck and chest, to whom should he apologize?” reads one paragraph.

“Jorge Menendez sprays poison on rocks for nine hours every day,” reads another.

A week later, and several pages into my next enterprise, I am still considering these strangle little graphs, still reflecting on what I should think McElroy is attempting to convey.

I’d be remiss to discuss tiny books without the context of their modern origins: the poetry chapbook. Bryan Borland’s latest collection, "Tourist" (Sibling Rivalry Press, 2018) is easily one of the most timely I’ve read in recent months.

Penned during the book tour for his second full-length poetry collection, "DIG" (Stillhouse Press, 2016), "Tourist" is a haunting snapshot in time, and Borland, the cultural observer. Capturing both urban and rural portraits of the United States during the 2016 election cycle, the poetry in this collection is largely inspired by his experiences on the road, and his need to write so palpable; it’s as though the words can’t leave him fast enough.

Poem "Indiana" from "Tourist."

Borland wrote “Indiana” after his reading was moved off campus for promoting “gay poetry.” Breathtakingly spare, yet ripe with the painful irony of too little progress, the source text for this erasure is one of Borland’s own, “Flawed Families in Biblical Times,” which first appeared in his collection, "My Life As Adam" (Sibling Rivalry Press, 2010). It was one of the poems he selected to read that evening.

His contemporary poetry—as it has in the past, for his relationships—examines the United States’ flagrant intolerance, largely embodied by the likes of candidate Donald Trump and the “Make America Great Again” movement, and explores the fragility of human life. “Chelsea Bomb,” the poem Borland wrote after the a pressure cooker bomb exploded in a New York City dumpster just blocks from him, is one of the most chilling in the collection, the final lines an evocative reminder of the very real, very tangible fears of our time.

you will worry

through the night

even when I call you

from a speeding car

even when

you know I’m safe

you are full of fear

my backpack is full of books

— excerpted from "Chelsea Bomb," Tourist

Taken together, these three small books comprise fewer pages than most full-length prose titles. They are spare in their language, yet dynamic in their undertaking. They steal my breath and my heart. They are only a small slice of the beauty contained in the world of modern literature, and yet, in the landscape of economy—which, in the era of instant gratification, we seem so often to be moving deeper into—they demand so little and give so much in return. Do your brain a favor and pick up a tiny book. I promise, you won’t only finish it—you’ll be rushing back for more.

Meghan McNamara a graduate of George Mason University's Creative Writing MFA program. She serves as the Director of Media and Communications for Stillhouse Press.

From Still to Shelf Pt. 4: Book Marketing For Artists

By Michelle Webber

When students want to enter the publishing industry after college, most of them picture themselves as editors. The leap is a logical one: those of us who pursue a BFA or MFA in writing spend so much time inside the manuscript that we forget the work must reach readers to achieve its true value. Many consider marketing and advertising the antithesis of artistic creation, that marketing’s only goal is to make money for the publisher, and that this process ignores the art of the book itself. But for Stillhouse Press, this notion couldn’t be further from the truth.

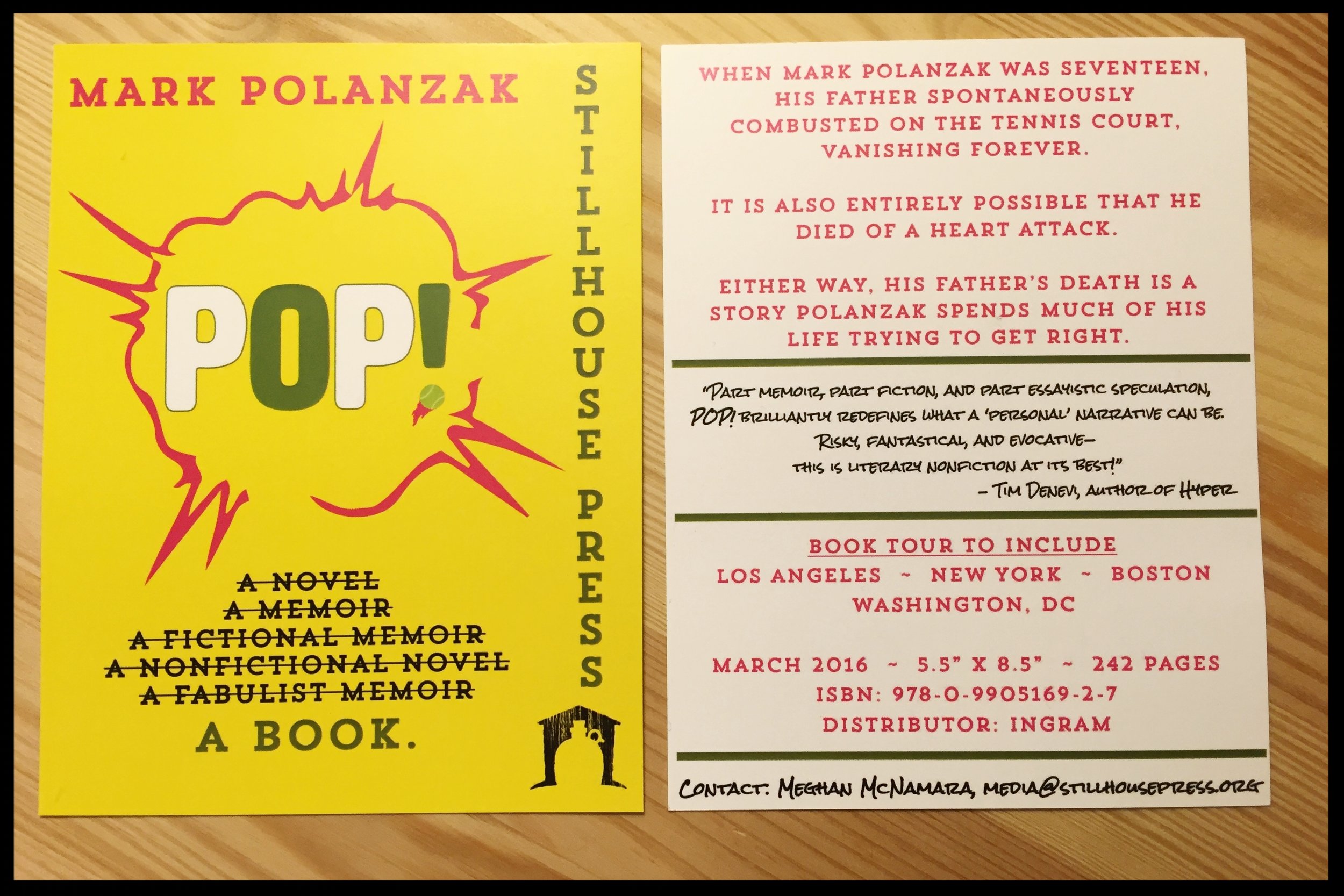

From a marketing brainstorming session for Mark Polanzak's POP! (March 2016)

Our marketing process begins only after we have first read the book in its entirety. We believe that to build an effective promotional strategy, there are several things we must know about the book that are best discovered by stepping into the shoes of the reader. The most important component of marketing is audience. So we ask:What is its genre? What kind of person would enjoy this book? To whom will it appeal? What other books does it remind us of? Another crucial element is the book’s unique appeal. What about this book is different from others in its genre? What is its greatest strength? If I had to pitch this book to someone in less than 60 seconds, what would I tell them about it? Answering these questions allows us to approach our promotional plan as readers and book lovers as well as marketing professionals.

Once we’ve read the book, our next step is to coordinate our timeline with Editorial. As soon as we acquire a book, we work backwards from the date of publication to plan deadlines, the first of which is the printing of Advance Review Copies (ARCs, or galleys). Publishers send ARCs to a number of contacts, including review outlets, trade publications, and potential blurbers (other authors who will read the manuscript and offer up a quote) to arrange media coverage and cultivate buzz. Each market has its own lead window (an industry term for the minimum amount of time before publication that an outlet will consider a book for review or coverage). At Stillhouse, we aim to prepare and begin shipping galleys four to six months in advance of publication.

After we’ve formed our timeline and the editorial team for the book has begun their developmental edits, we schedule a meeting with the author to talk about their publishing and writing contacts, their list of potential blurbers, and the use and development of their social media platforms. We also discuss any upcoming publications, plans to submit new writing, and career or occupation changes so that we can leverage every advantage and increase an author's visibility. Every author brings something new to the conversation and every book is different, so we refine and tailor our marketing strategy accordingly.

Over the next several months, the marketing team works closely with the author and managing editor to build an exhaustive list of contacts for media and reviews. Each list is pulled from a central database that we continually update with new markets and publication staff changes. Once every contact, email address, and mailing address has been vetted and approved, we begin querying. This is largely the same process that authors go through when querying agents and publishing houses, only in reverse.

As soon as galleys are printed, proofed, finalized, and shipped to us, we begin sending packages to media. In this package, we include an ARC and relevant publication data. We prefer to include all publication info in the form of a postcard, rather than the industry standard press release, which is often discarded, unread. We strive to ensure that the concept driving the artwork and marketing materials is consistent between the galley and the product. This process often continues on a rolling basis until the month of publication.

Once we begin to receive notifications of coverage from some of the outlets that read the book and want to feature it either in a review or in an interview with the author, the marketing team coordinates timelines with the market and the author, and adds items to our roster for social media.

While cultivating media coverage is one of our most important responsibilities, there are several more obscure components of our department that are just as essential to the success of the press. Our Social Media Editor is responsible for writing and scheduling weekly posts on Facebook and Twitter that not only increase awareness of our titles, but that also participate in a dialogue of literary citizenship. Successful media campaigns aren’t paved with purchase-centric posts. The most effective strategy is to participate in relevant conversations, share the successes of your friends in the publishing industry, and comment on recent events. The best way to maintain a strong follower base is to engage the target audience’s community.

Maybe Mermaids & Robots are Lonely book signing at the 2016 Brooklyn Book Festival. From top left to right: Editor, Marcos L. Martínez; Managing Editor, Justin Lafreniere; Communications Director, Michelle Webber; bottom: author, Matthew Fogarty.

The marketing team also plans book tours and promotional events, both in the local area and across the country. Some of our events are recurring each year, including readings at Fall for the Book, AWP, and other literary conferences. If the event is local, the marketing team services and coordinates logistics.

Marketing is perhaps the most collaborative process at Stillhouse Press. Members of our team work closely with authors, managing editors, stakeholders, and industry professionals to ensure that our titles not only sell but that they also reach readers who value them. By taking into consideration the strengths and audience of the work, the network and media presence of our authors, and the literary climate into which each project is released, we are able to construct a plan that pleases all parties. Marketing, then, isn’t just about making money for the press. It’s about making happy authors, too.