by Stefan Lopez

So, your manuscript has been selected for publication. You’ve done it! You sold your book! At first, this might seem like the most difficult part of the process. In reality, though, acquisition is only the beginning of a much longer—often time more arduous—path to publication.

At any press, preparing a manuscript for publication and getting in front of prospective readers takes a lot of effort on behalf of both the author and the publisher. From submissions to acquisition, development to release—a year-long process, at least—is an all-hands-on-deck endeavor. So, what should a debut author expect from their publication experience? I sat down with Stillhouse Press director of media & marketing, Meghan McNamara to find out.

“There are writers who just want to put their heads down and write, and leave everything else to others, and we just don’t live in a world where that’s possible,” McNamara says, especially as it relates to small press publishing.

“Since we only publish two to three books a year, we have more of a chance to work closely with the author and really refine their work.”

Perhaps the first thing to know about small press publishing is that it’s not uncommon for members of the press to take on multiple roles, especially when they are first starting out. Unlike the big houses—Hachette, HarperCollins, Macmillan, Penguin Random House and Simon & Schuster—who have a whole host of people dedicated to the many different tasks involved in publication, small presses rely on the resources of a few dedicated individuals.

“My roles have changed so much over time, from book promotion to distribution and wholesale orders, and running the website. It’s kind of a mix of all things administrative and promotional,” McNamara says. For the first year, she said, “during the off season, Marcos [Martínez] and I were often the only ones in the building.”

Though there are positives and negatives to this, the small team size often leads to a greater intimacy with a project, as everyone has a hand in developing and promoting it. What small presses might lack in reach and manpower, the staff makes up for in time and care.

“Our press has more of a craft focus,” she says. “Since we only publish two to three books a year, we have more of a chance to work closely with the author and really refine their work.”

Central to the development and promotional process is the galley (also known as an ARC, or advanced reading copy)—essentially the first draft of the final book.

“First you have the manuscript that goes through the editorial process. Once everyone—author and editors—has signed off on it, we send that draft to the printer and it becomes the galley.”

Just like McNamara herself, the galley serves several functions. On the editorial side, it is the last chance for edits to be made, both internally and externally. Editorial interns use it to make their final edits, scanning for grammar or content inconsistencies that might have been missed in the final manuscript edit.

On the marketing and media side of things, the galley also functions as a first glimpse for prospective media, including advance interviewers and reviewers. Media responses both generate buzz for the book and give the publisher a sense of what a general audience response might be.

Image Courtesy of S.K. Dunstall

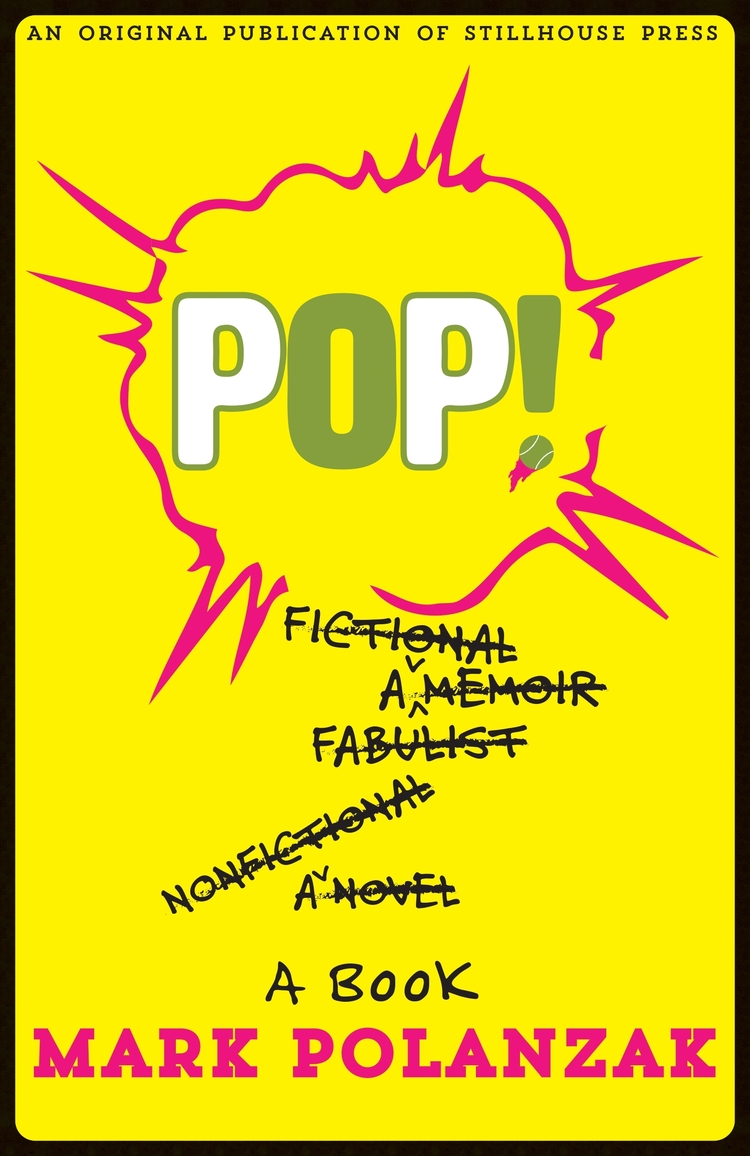

Galley covers were once a plain and simple endeavor—often plain brown and printed with the title and author’s name—though small presses like Stillhouse now use the galley as a debut cover run of sorts.

“When Stillhouse was first starting out, someone once told me that it takes a person upwards of three times to see a book before they are intrigued enough to buy it,” McNamara says. “It just made sense we should take advantage of this brand opportunity.”

Thus, the galley cover is, in many ways, the perfect opportunity to start conveying the book’s brand.

“Personal appeal is almost always the best way to find support for your book.”

The author is also on the front lines of promotion. Though this networking might seem daunting to many authors, it’s an integral part of the success of a small press title. Through public readings and interviews, author profiles and social media interaction, an author becomes the face of their book. Behind the scenes, they network with fellow literary contacts and acquaintances to shore up support. If there are blurbs — as the industry folk call a book’s cover quotes — they often come from writers or editors the author has worked with or has reached out to personally.

“A personal appeal is almost always the best way to find support for your book,” McNamara says.

And the support cuts both ways, she adds, noting that the books which find the most support are those written by authors who interact with and advocate for their literary peers.

“People want to engage with you if you’re interesting and active, but if you just start a Twitter account to only promote your book, you won’t get a great following.”

While they wear very different hats within the realm of Stillhouse, McNamara’s advice certainly mirrors that of fellow founding editor, Marcos Martínez.

“It’s important to build a community of readers,” Martínez told me during an interview a few months prior. “People will support you if you support them.”

In other words: the best way to become a successful writer is to develop a community.

“Every author has a following, even if it’s just friends of the writer or people who casually follow their work online,” he says.

The world of small press publishing is exactly that: small. Support others so that when it’s your turn, they will support you.