THE HOLIDAY SEASON IS UPON US!

As 2018 steadily approaches, we've go a few drink recommendations

to pair with your favorite Stillhouse Press selections.

Carmen Gillespie’s latest collection interrupts the everyday to bring us the spiritual visitations of Sally Hemings, her half-sister Martha Wayles Jefferson, and other famed and forgotten residents of the Monticello plantation. These poems reach into the distant past to unearth songs of pain and longing, weighty with the long history of American silence that continues to circumscribe our lives today.

Monticello Spiced Rum Punch

History is a tough pill to swallow. For this, we'll need plenty of rum. Adapted from this Bon Appétit recipe, this rum punchis made to satiate partygoers and historical ghosts alike.

Ingredients

1 cup George Bowman rum

1 cup fresh grapefruit juice

1 cup meyer lemon juice

1/3 cup Luxardo maraschino liqueur

1/4 cup simple syrup, 2 teaspoons bitters (Angostura works well)

1 cup sliced mangoes

1 cup of assorted citrus fruits, sliced into rounds

Directions

Add all ingredients to bowl. Mix well.

Chill.

Serve with ice.

Maybe mermaids and robots are lonely. Maybe stargazing dinosaurs escape extinction, and ‘80s icons share their secrets and scams. A boardwalk Elvis impersonator declines in a Graceland of his own, Bigfoot works as a temp, families fall apart and come back together.

The Elvis Peach

Rumor has it, Elvis once reportedly drank so much peach brandy it nearly killed him. Adapted from Food & Wine, this brandy-based brew will take you from fabulist faraway worlds to Great Recession realism in a single sip.

Directions

Add the rum, peach brandy, black tea, simple syrup and lemon juice to a large pitcher.

Stir, add the water and stir again.

Refrigerate until cold.

Serve in collins glasses with citrus garnish.

Ingredients

4 ounces Mt. Defiance dark rum

5 tablespoons simple syrup

4 ounces brewed black tea

4 ounces lemon juice

Splash of water

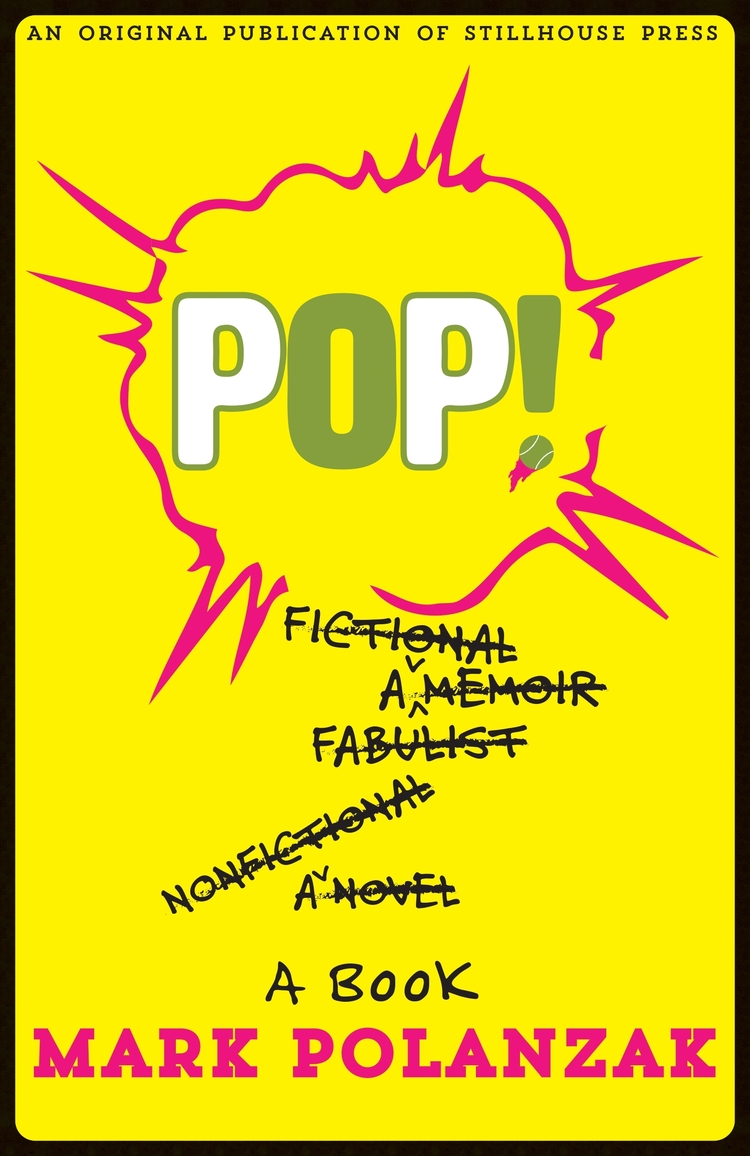

When Mark Polanzak was seventeen, his father spontaneously combusted on the tennis court, vanishing forever. It is also entirely possible that he died of a heart attack.

The Gin Fiz Wallop

Like Polanzak's hybrid memoir, each slurp of this fizzy little number is scarcely what you might expect.

Ingredients

Combine 2 ounces Catoctin Creek Watershed Gin

Juice from 1/2 a lemon

2 teaspoons of simple syrup

Club soda

1/2 package of Pop Rocks

Pinch of granulated sugar

Directions

On a small plate, combine Pop Rocks and sugar

Wet rim of highball glass with a slice of lemon

Add gin, simple syrup, and lemon juice to cocktail shaker and shake well.

Strain into glass, careful not to disrupt the rim.

Top with club soda and serve.

Bryan Borland’s third poetry collection examines what it means to dig—to undertake the intense labor of unearthing the personal/political/artistic self and embracing the consequences of that knowledge.

The "DIG This" Manhattan

We're craving bourbon for this sexy love story, the way readers crave

their next Stillhouse fix. Adapted from this Ted Allen cocktail, you need this Manhattan like you need blood in the throat.

Directions

Add ingredients to cocktail shaker.

Shake well.

Rub an orange pee along the rim of your martini glass.

Strain drink into glass.

Garnish with one (or two!) cherries.

Ingredients

2 ounces Bowman Brothers bourbon

1 ounce Mt. Defiance sweet vermouth

1 dash of bitters

1 orange peel

Luxardo cherries.

For poet Anna Leahy and scientist Douglas R. Dechow, quintessential children of the Space Age, love for each other and love of space are inseparable. The moon landings, the shuttle program, the prospect of manned travel to Mars: each stop in humanity’s journey to space has marked a step in their ongoing love affair with each other and the cosmos.

[Generation] Space Punch

Adapted from the Belle Isle Craft Sprits recipe, this spacey brew will have you reaching for your dearest... or maybe just another mug of this stellar concoction.

Directions

Combine ingredients in punch bowl.

Add ice.

Garnish with rosemary and serve immediately.

Ingredients

1 bottle Belle Isle Ruby Red Grapefruit

2 bottle sparkling wine (try Virginia's Horton Sparkling Viognier)

5 ounces St. Germain elderflower liquer

5 ounces white grapefruit juice

3 ounces lemon juice